Sue and Terry Atkinson

‘Recent Work’

28 February to 11 April 2025

Sue Atkinson, Show Home, Charcoal and collage on canvas, 101cm x 126.8cm, 2024-25

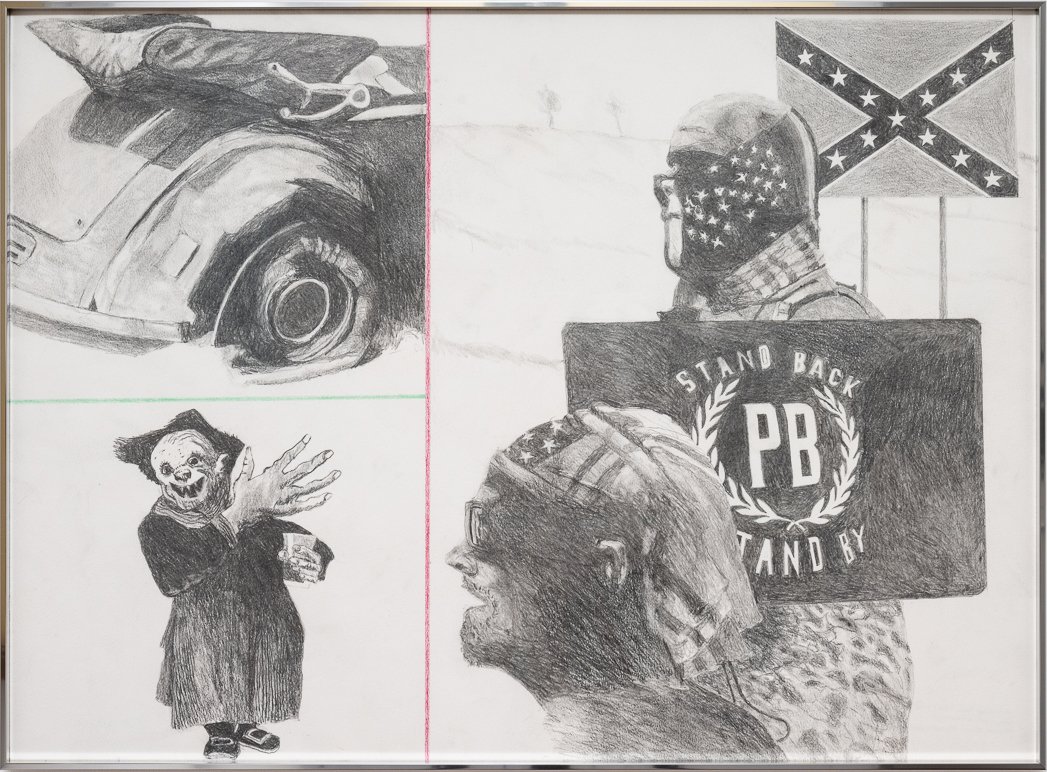

Terry Atkinson, American Civil War: Study 81. Study for a painting. Remind those Motherfucking Proud Boys that, in the end, Heydrich got a flat tyre. Goya says Hello!, Pencil on paper, 55.8cm x 76.4cm, 2020-21

Moon Grove is pleased to present ‘Recent Work’ by Sue and Terry Atkinson, an exhibition that combines drawings and paintings with a prescient relationship to current geopolitical events. Both artists, who are working hard in their mid-80s, have focused on overtly radical subject matter since the 1960s, with the potency of their work becoming stronger over time.

Sue’s Show Home (2024-25) and Open House (2025), for example, two parts of a new series initiated in 2024 fashioned in the sombre medium of burnt graphite on canvas[1], take the ruins of the Gaza strip as their starting point to extend a historical and political narrative on British and American Imperialism. The first work presents a composite image of the shattered Palestinian territory collaged with ghostly images of a bucolic English landscape – a Norman church, a thatched cottage, and a swan on a lake – which appear mirage-like in the foreground, clearly referring to the effects of the recent near future proposed by President Trump for the territory to be converted into prime real estate.[2] With both works titles taking a friendly swipe at the site of the exhibition by using the minor of the suburban home to comment on major of mainstream geopolitical aggression – a small Georgian house that doubles as a gallery to show contemporary art – the domestic setting combines with American domination and reoccurring tropes or signifiers of fascism, such as the motif of the eagle. If this uncomfortable vision by Sue folds the past, present and future to dwell on the clearest and unfiltered proposal for ethnic cleansing in recent memory, then equally, Show Home’s focus on the past in the present serves to produce a ‘pre-post-erously’[3] terrifying glimpse of the future for anyone except those in the extremist centre.

SAS Landscape: Made for the Bedroom (2011), meanwhile, hints at Sue’s lack of concern for holding a professional profile as an artist within the narrow confines of the contemporary art establishment, with the painting made not to be shown in a traditional public institution or commercial gallery. Instead, the work’s aim is simply for domestic use, its natural environment existing within a family home. Personal significance, connected to this context alongside military history, again becomes perceptive, especially regarding the Middle East. Sue’s father, Arthur, for example, was a member of the British 6th Airborne Division in Palestine between 1946 and 1949, and like many of his colleagues, found the experience deeply uncomfortable. Copies of Arthur’s Egyptian banknotes from the period have been inserted into an Uncle Sam moneybox – picked up by Sue and Terry on a visit to New York in 1969 – positioned on Moon Grove’s front room’s mantelpiece.[i] Further works by Sue, such as Addicted to Poppies (2022) focus on the English landscape, as well as WWI, the drug trade in Afghanistan, and by proxy, a focus on feminist concerns connected to the Taliban’s treatment of women.[4]

In turn, Terry’s work comprises a selection of his recent ongoing American Civil War series, which, in an elementary sense, draws parallels between the American Civil War (1861-1865) and the current tensions in the US. A closer examination complicates any simple connection between different points in time and history, alongside an encyclopaedic examination of the visual culture of conflict between the union, the confederacy and related artefacts. In a revelatory sense, art historical moments and popular cultural references combine with major world events – including the Civil Rights Movement, Goya, Star Wars, and The Simpsons – to produce an antagonistic disjunction between forms of language and styles of literature and theory, including science fiction, gothic horror, and philosophical aesthetics, to establish a clear vision of where we stand in this point in history. This is also evident in Terry’s essay-like titles – part of the works themselves – including the following text, which again points to time, duration, dislocation and breakdown: American Civil War: Study 37. A masque Goyaesque time-travelling Burraghost encounters a problem with its time-travelling function, and by virtue of this malfunction finds itself, instead of returning to the Quinta del Sordo at the time of its demolition in 1909 (the Burraghost’s aiming point), alighting at the burning city of Charleston on February 15, 1865. Behind the Goyaesque float a row of Hollywood celluloid digital figures (also time-travellers) culled from Star Wars data bank, but more accurately controlled, that are locked into the same timeframe. It is perhaps hard to detect whether or not these figures (both the Burraghost and the Star Wars figures) are floating above or are somehow attached to the Earth’s surface and this perhaps is a sign of the artist’s incompetent drawing. Meanwhile on the other side of the burning horizon, Sherman’s Union columns, although not in the picture, stream into Charleston.

After an eighteen-year hiatus, this exhibition follows its spiritual predecessor Sue Atkinson ‘Greenham Work’ / Terry Atkinson ‘Irish Work’, held at International Project Space in Bournville in 2007, a project that similarly used direct political content to activate an energetic relationship with its site.[5] If a conversational form of ‘back and forth’ exists between these two exhibitions – one held in 2007 and the other in 2025 – then a conscious transtemporal voyage is clear in both artists current series of work. Sue’s painting Back (Bat) to the Future with Poppies (2021), again uses poppies and landscape to conjure different times and locations, while the sequential looping of Terry’s Time-travelling postcard from one civil war to another and vice-versa: ACW-RCW, into the future and back – endlessly (2019), focuses on the mechanical regularity with which polarised populations come to oppose one another in the US, the message being that history continues to repeat itself, on a wider level, time after time.

Sue Atkinson: ‘I was born in Birmingham in 1946 and lived on the periphery of the Bournville estate. Although I was not raised a Quaker, the culture and values of Quakerism influenced the domestic and workplace environment. The visual was controlled. Televisions were not encouraged and the residents, the ones who had TVs, were urged to hide their aerials. There was a cinema in the factory and an art school. I won an art prize awarded by Cadbury’s. My parents were told by my secondary school, which had ‘Bournville’ in its title, that art for girls should be just a hobby. The question of my artistic value has been difficult for me to escape. I opted to pursue Graphic Design (Visual Communication) at Birmingham College of Art between 1963 and 1968. I came to realise that anything I did served a capitalist economy, an economy Cadbury’s is embedded in, but the Cadbury culture then leaned towards the social and the communal with the aesthetic influenced by the ascetic culture of Quakerism. Many men living on the estate were conscientious objectors and didn’t go to WWII. Vegetarianism was not uncommon. I think this tension between artistic restriction and the insidious power of the establishment in a quasi-liberal democracy, and opposition to unnecessary wars and violence have shaped my artistic practice.’

Terry Atkinson (born 1939) is an English artist. He was born in Thurnscoe, near Barnsley, Yorkshire, and lives in Leamington Spa with his wife, artist Sue Atkinson, with whom he frequently collaborates. In 1967, he began to teach art at the Coventry School of Art, while producing conceptual works, sometimes in collaboration with Michael Baldwin. In 1968 they, together with Harold Hurrell and David Bainbridge, who also taught at Coventry, formed Art & Language, one of the most influential collectives in contemporary Western art. Atkinson stopped teaching at Coventry in 1973 and the following year left Art & Language. He has since exhibited under his own name, including at the 1984 Venice Biennale. In 1985 he was nominated for the Turner Prize. Atkinson's work is held in many collections, including Tate.

[1] Sue has previously used coal dust as a medium in her works connected to the UK’s Minor’s Strike in the mid-1980s.

[2] President Trump has called this plan the ‘riviera of the middle east’.

[3] Hal Foster, Robert Garnett and others have used the term ‘pre-post-erous’ in their writing on contemporary art to suggest a focus on ideas of the past connected to the future in a speculative manner.

[4] Feminist tropes have echoed in Sue’s work since and before she started her series of work based on her participation with the women of Greenham Common.

[5] Apart from Birmingham holding the largest Irish population in the UK – a fact related to Terry’s work for this exhibition – Sue’s Greenham work held a deeply personal significance to the site of the exhibition in Bournville, what she perceived as her awkward relationship with the area that had been built on Quaker principles. Please refer to Sue’s biography for more details.